MP Econ Issue 20: China’s First Half Economic Outlook

In this special feature, we are including our 1H2024 Outlook. The PDF report can be downloaded here and will also go live on our website tomorrow.

Slower Growth to Drag On in Dragon Year

1H2024 Key Takeaways:

In March, Beijing is expected to set a lower growth target of 4.5% for 2024, signaling a more challenging environment and managing expectations around growth.

That’s because all key drivers of growth—investment, consumption, and exports—face even more daunting challenges in 1H2024. In particular, the unraveling of the local debt crisis will put more downward pressure on growth.

But like in 2023, the Chinese government won’t be trigger-happy with stimulus anytime soon, instead riding out the bumps until it believes it must put a floor on growth.

As such, 2024 growth will likely be U-shaped, with 1H2024 weaker than the second half when the chance for stimulus rises.

Last year played out largely along the lines we expected, with the economy coming out of the gate with decent growth, only to lose momentum and flatline by the second half. Although China technically met its 2023 growth target, peeling back the onion reveals continued weakness in the absence of stimulus. That stimulus won’t arrive in 1H2024 either, as we would caution against reading too much into headlines about imminent stimulus.

Like in 2023, there may be some monetary and fiscal support at the margins, but they won’t be sufficient in overcoming the struggles the economy faces in 1H2024 to meaningfully boost growth. All the factors that weighed on the economy in 2023 are still present in 1H2024, except they are likely to worsen. When it comes to investment, the deteriorating local debt problem will drag it down. On consumption, the one-off unleashing of pent-up demand that temporarily bolstered the economy in 2023 will have dissipated. Finally, while the export contribution to growth was already negative in 2023, the increasing likelihood of trade tensions isn’t likely to reverse this trend in 1H2024.

It appears that Beijing is cognizant of a tough year ahead—despite its public rhetoric to the contrary—and will look to manage expectations on growth by setting a lower target of 4.5% at the March National People’s Congress (NPC). Such a target also implies Beijing isn’t likely to deviate much from the playbook it adopted in 2023: withhold stimulus until it believes growth might crater far below the target.

Growth Drivers Will Lose Momentum

Investment: Local Governments Between a Rock and a Hard Place

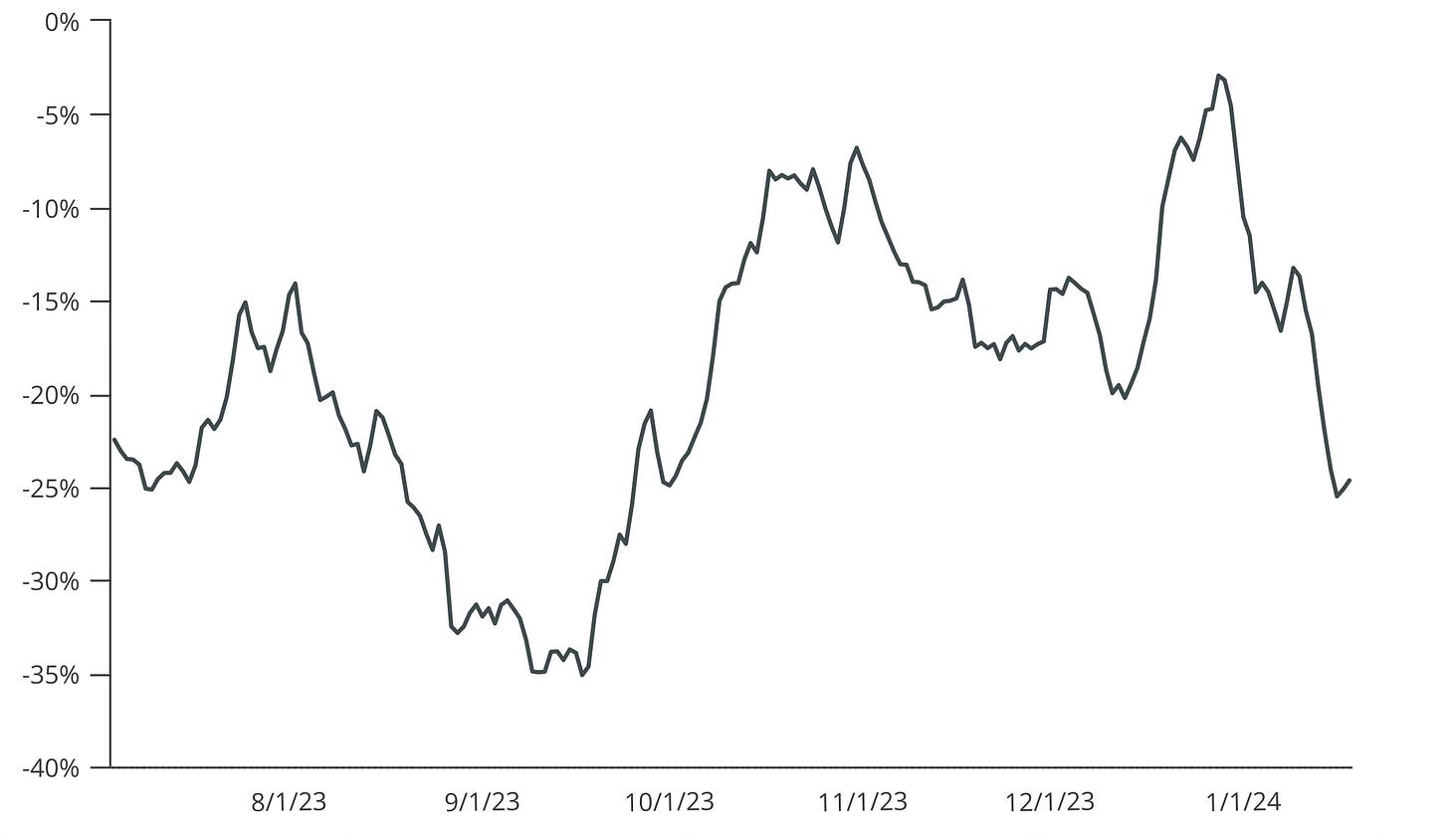

While Evergrande is becoming “EverMeh”, such an outcome should not have been that surprising. It is simply another data point in a bleak picture of China’s property sector. Despite supportive measures in 2023, property sales nonetheless declined 13% from 2022. Sales were particularly weak at the end of the year, down 23% in December 2023 year-on-year, and first-tier cities weren’t exempt from the sales slowdown either (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. First-Tier Cities’ Property Demand Down Since Late 2023 (% growth, y-o-y)

Source: Wind and MacroPolo.

The property hard landing, drawn out as it is, will of course affect private investment. But what’s more concerning is the unraveling of the local debt problem that will affect investment even more. Beijing’s financial support in 2023 may have stabilized local government finances for a while, but the reprieve is likely temporary as local debt will once again deteriorate in 1H2024. This is because Beijing remains hawkish on deleveraging and continues to put local governments between a rock and a hard place.

At the one end, Beijing still insists that local governments pay the interest on their debt, even if it has allowed a temporary delay on paying the principal. On the other end, Beijing won’t allow local governments to borrow more to pay back the debt, because that would of course raise the leverage. These mandates hardly give local governments any breathing room because their fiscal conditions are so bad that they cannot meet their interest payment obligations. If the borrowing rule is strictly implemented, that will lead to an annual 2 trillion yuan ($416 billion) cash shortfall for local governments, based on our estimates. That means local governments will have to cut their spending by a similar amount.

Consumption: Chinese Consumers Turning More Cautious

While growth in 1H2023 was in part buoyed by the end of Zero-Covid, that was a one-time phenomenon that won’t be replicated in 1H2024. Moreover, there are worrying indicators of Chinese consumers tightening their purse strings again. This can be seen in the savings rate.

The household savings rate has a significant impact on growth. By our estimate, had the 2023 household savings rate remained at its 2022 level, growth in 2023 would have been at least 1.2 percentage points lower—below 4% instead of 5.2%. However, although the savings rate declined year over year, the 2023 savings rate was still 2 percentage points higher than 2019, so growth would be even better if the savings rate were to return to pre-pandemic levels.

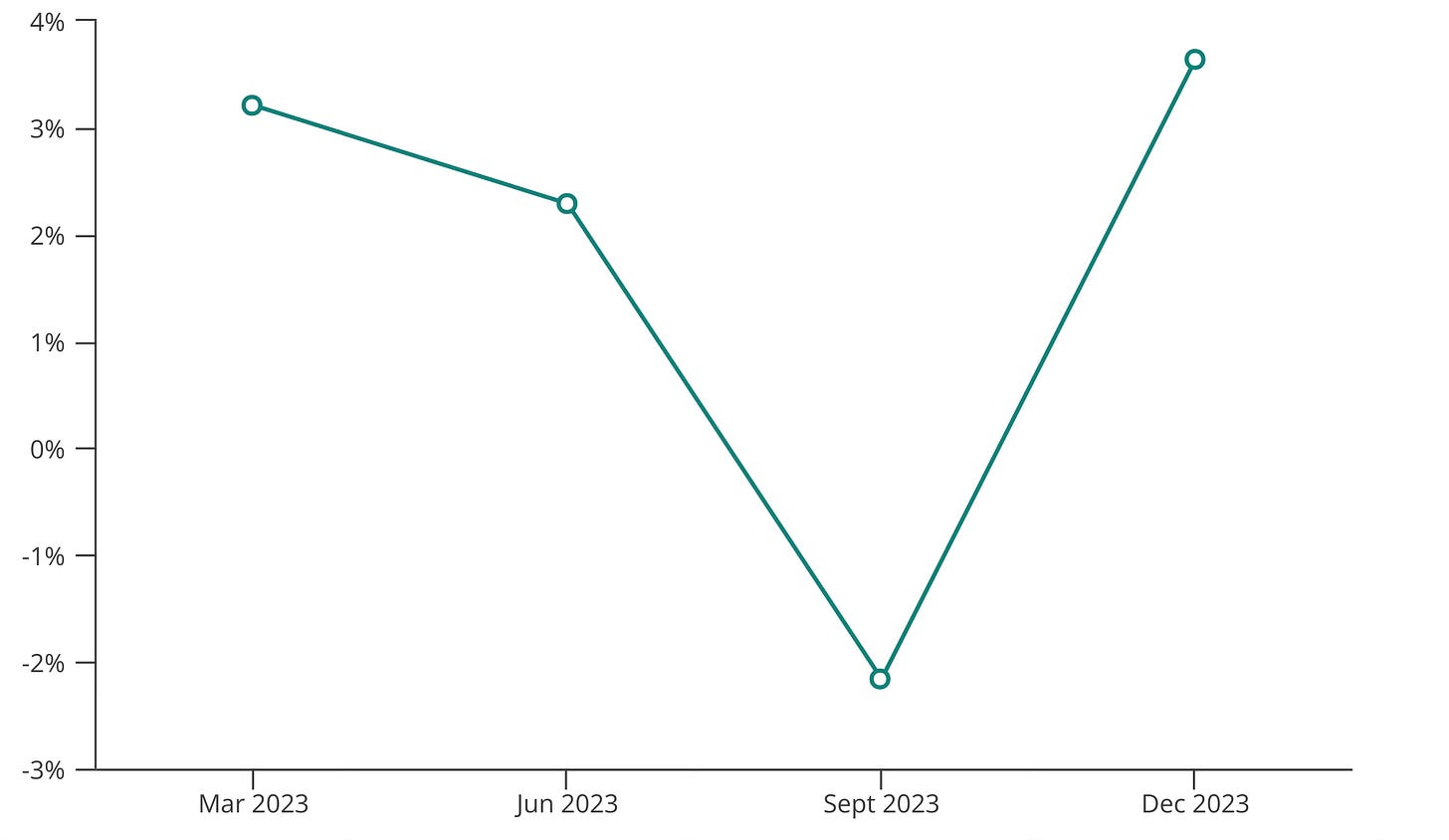

But that looks far from achievable judging by how 2023 ended. While the household savings rate declined for two quarters in 2023, it bounced back up significantly in 4Q2023, which was four percentage points higher than 4Q2019 (see Figure 2). This suggests that Chinese households drawing down their savings reflected one-off factors, such as spending on travel over the summer of 2023, the first summer since the pandemic Chinese citizens could travel freely.

Another reason the savings rate isn’t trending in the right direction is because household income growth is also under threat amid a slowing economy. Compared to pre-pandemic levels, Chinese household income growth is down by 2 percentage points. Continued household consumption weakness suggests it will contribute less to growth in 1H2024.

Figure 2. Household Savings Rate Shows Little Sign of Returning to its 2019 Level

Note: This chart shows household savings rate relative to same period in 2019. Positive reading means higher saving rate.

Source: Wind and MacroPolo.

Exports: A Less Friendly External Environment

With the exception of electric vehicles (EV), solar panels, and Russia—which have dominated headlines—China’s total exports actually contracted by 5% in 2023. The so-called “new three” (EVs, battery, and solar panel) exports and exports to Russia increased by $37 billion and $34 billion, respectively, in 2023. So while news headlines focused on the performance of sectoral exports, the macro picture for exports was not so stellar in 2023. And we see two good reasons to believe that exports won’t fare much better in 1H2024.

One, the growing drumbeat of protectionism in G7 countries doesn’t bode well for Chinese EV and solar exports. Two, the rapid expansion of exports to Russia in 2023 has likely run its course, as Chinese products already account for ~40% of Russian imports at the end of 2023, compared to ~20% before the Russia-Ukraine war. It is difficult to imagine Chinese exports gaining much more market share in Russia’s total imports. As such, Chinese exports overall will likely find a less friendly external environment in 2024.

No U-Turn, but U-Shaped Growth in 2024

Beijing seems to be aware that the growth environment will be more challenging, as we expect it to set a modest growth target of 4.5% in at the March NPC. In fact, central fiscal and monetary policies in 2024 further suggest that Beijing isn’t moving to a pro-growth stance anytime soon.

Beijing’s one trillion yuan ($140 billion) bond issuance to finance new projects like affordable housing and rehabilitating rural backwaters certainly provided some excitement for stimulus. But reading between the lines, the central government’s priority remains having a stable government debt to GDP ratio. That priority should dampen enthusiasm for robust stimulus because it implies these new infrastructure and investment initiatives should be seen as ways to offset declining local fiscal spending rather than stimulus.

When it comes to monetary stimulus, expectations should also be tempered. There could well be more reserve requirements ratio cuts in 1H2024, but that won’t translate into faster credit growth. That’s because credit policy in 2024 will likely focus more on “better capital” rather than “more capital”, in line with the top leadership’s insistence on “high quality” instead of high quantity growth. The focus on improving capital allocation, therefore, will likely come at the expense of credit growth.

Pushing credit expansion also makes less sense when China’s banks have more or less hit their limits on extending new credit to local governments and the property sector, both of which carry high risk premiums. Continued lending will only worsen banks’ financial health, so Beijing is opting to focus on the productive use of capital to mitigate further downside risk to the financial system.

The combination of growth headwinds and continued inaction on stimulus means that China’s growth for 2024 will likely end up being U-shaped. In other words, both growth and local government debt will deteriorate in 1H2024, which would provide a wake-up call for Beijing to take more action, including potential bailouts to local governments, to materialize in 2H2024.

We will reassess our holistic view on the Chinese economy in the second half of the year, while continuing to weigh in on the developments that really matter between now and then.

Houze Song is a fellow at MacroPolo. You can find his work on the economy, local finance, and other topics here.