MP Econ Issue 11: Who’s Paying for the Property Crisis? Not Local Governments

Recent signs have reinforced the fact that Beijing is reluctant to bail out troubled property developers, a case I made previously. The July Politburo meeting, for example, declared that the responsibility for rescuing unfinished housing projects falls on the shoulder of local governments. So we should expect a flurry of local government-designed bailouts over the next few months.

The effectiveness of these local bailouts will determine how Beijing will eventually respond. Yet judging by Zhengzhou’s plan, the provincial capital of Henan with the most unfinished housing projects, it does not appear that local governments are up to the task.

On paper, Zhengzhou has allocated 80 billion yuan ($12 billion) for the bailout. That breaks down to 10 billion yuan ($1.5 billion) from the city government, with an addition 70 billion yuan ($10.5 billion) from the local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) and banks.

That seems ambitious on face value, but upon closer examination, the plan is problematic on two fronts because it is premised on the city government passing the buck on bailing out developers.

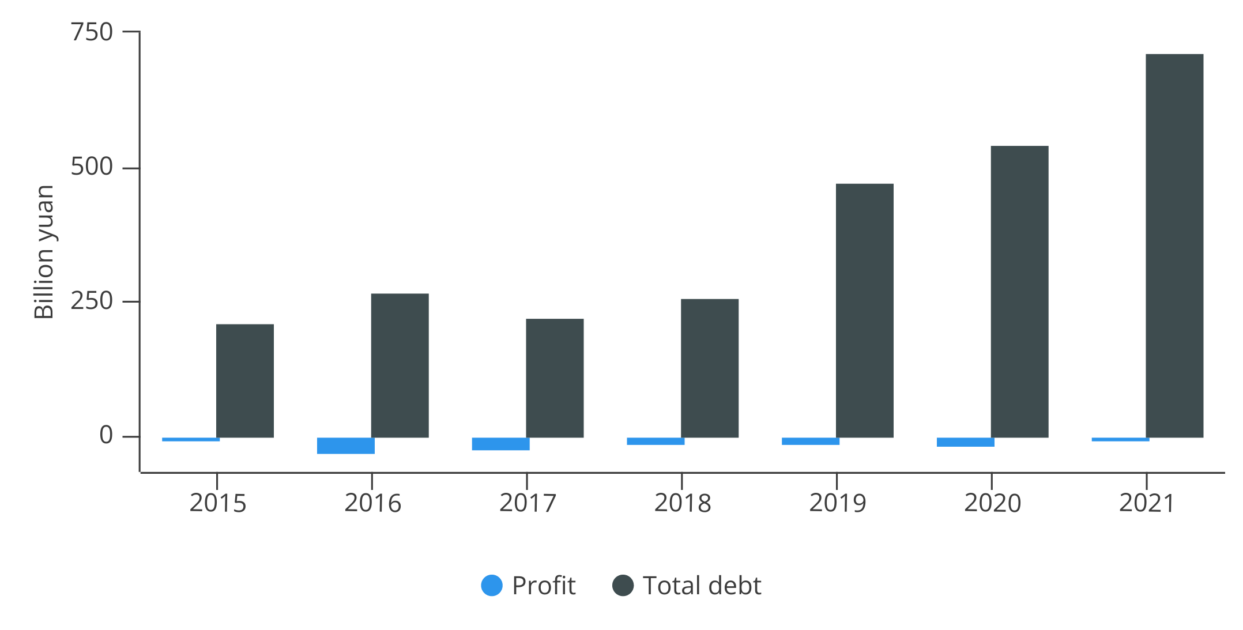

For one, a key part of the plan is to use LGFVs that are broke to bail out broke property developers. Indeed, Zhengzhou’s LGFVs are likely in worse shape than the property developers they’re supposed to rescue. For instance, the city government is calling on LGFVs to contribute at least 20 billion yuan ($3 billion) to the bailout fund, but the LGFVs themselves have racked up more than 100 billion yuan ($15 billion) in losses and tripled their debt to more than 700 billion yuan (~$105 billion) since 2015 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Zhengzhou LGFVs Keep Losing Money While Tripling Their Debt

Note: Profit is measured by net operating cash flow.

Source: Wind and MacroPolo.

What’s more, the Zhengzhou government wants to use property developers’ own assets to bail themselves out. The operating principle of the plan is that the bailout fund will buy good assets from struggling developers and allow them to use that money to complete unfinished housing projects. In other words, the city government is expecting the developers to help themselves.

But that relies on the faulty assumption that any developer would actually want to participate in this scheme. Those developers that require bailouts are likely already insolvent, so the risk of future losses is shifted onto the creditors. If anything, these property developers would rather wait out the downturn than part ways with their good assets, the only chips they’ve got left to potentially mount a comeback once the market recovers. Just look at Evergrande, it is still managing to muddle throughmore than a year after its unraveling.

Both of these ideas are likely unworkable because they reflect the Zhengzhou government’s underlying desire to pass the buck on paying for the bailout. It’s putting the responsibility on LGFVs, which in turn are leaning on property developers to bail out themselves with their own assets because LGFVs can’t afford to lose more money. Developers, in the meantime, have no desire to have local governments take over their business, preferring to salvage what’s left and wait for handouts from the central government.

They may have to wait for quite some time, however. No major central government bailout is on the horizon, because Beijing will likely wait and see how local governments proceed for some time. But that means there’s going to be runway for other cities to more or less replicate Zhengzhou’s faulty plan that will neither solve the property crisis nor please constituencies.

How bad does the problem have to get before Beijing acts is unclear at the moment. But so long as these local bailout plans rely on passing the buck among stakeholders, breaking this impasse will likely require Beijing to step in much more forcefully, reluctant as it may be.

That’s because the longer Beijing lets these local bailout plans run, the starker the choice it becomes: either continue to let the property market languish or intervene more dramatically to stabilize the sector.

Houze Song is a fellow at MacroPolo. You can find his work on the economy, local finance, and other topics here.