In our recent outlook, I estimated that the property sector’s correction will shave just 0.6 percentage points off of China’s headline growth. This assessment of a modest growth impact is predicated on the assumption that there has been systematic exaggeration of both property and land revenue.

That exaggeration is a result of two factors: 1) an accounting issue in official statistics that double counts property developers’ revenue; 2) “fake” transactions that are inflating land sales across provinces.

Extrapolating from these factors, my relatively conservative estimate is that total property and land revenue are likely exaggerated by 15% and 30%, respectively. In the aggregate, this means property and land revenue combined accounts for 2 percentage points less of GDP than what’s in the official statistics.

If the actual size of the property sector is smaller than on face value, then it has less of an impact on growth. However, cooking the books on land sales affects local governments’ pocketbooks. If land sales have been consistently inflated, that means local governments have been taking in less revenue, making them less capable of servicing their debt and raising financial risks.

Now let’s walk through how and why there has been exaggeration of property and land revenue, as well as its implications for financial stability.

Property sales are subject to double counting

Although Chinese property developers usually report total sales to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), these figures aren’t particularly reliable. Specifically, the sales figure is likely the result of regular double counting.

Here’s how it basically works. The NBS has ~100,000 developers in its sample, or roughly half of all developers. Determining total revenue based on a sample slice of the sector isn’t unusual, and is in fact a standard practice that NBS adopts for many other sectors. But this method no longer works well in the context of a recent development in the property sector.

That is, JVs have become a prevalent business model for property developers. For instance, using minority stakes as a proxy, JVs have gotten bigger in size since 2012. Meanwhile, NBS data show that developers not in its sample are accounting for a larger portion of total revenue (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Growth in JV Size Appears To Be Inflating Property Revenue

Note: Inflated revenue refers to revenue of developers not in the NBS sample, which includes the majority of JV revenue. JV size is proxied by minority interest (% of parent company equity).

Source: Wind and MacroPolo.

What’s troubling is that there appears to be correlation between the growth of JVs and the increase in revenue. But that should not be the case if the JVs’ revenue is already included under the respective parent company. Based on analyzing data from the 2018 and 2013 general survey, this trend implies that NBS has been linearly extrapolating total revenue based on the number of entities, failing to recognize that JVs’ revenue should not be counted separately.

So what’s the effect of this double counting of JVs on total revenue exaggeration? About 2.4 trillion yuan (~$380 billion). Or in other words, true developer revenue should be about ~15% less than the NBS reported figure. (This is based on the fact that the 100,000 developers in the NBS sample, all of which are listed, account for ~60% of total developer revenue. And since JVs are estimated to account for about a quarter of the total revenue of listed developers, that means JVs should be about 15% of the revenue of developers in the sample.)

Land revenue is inflated by cooking the books

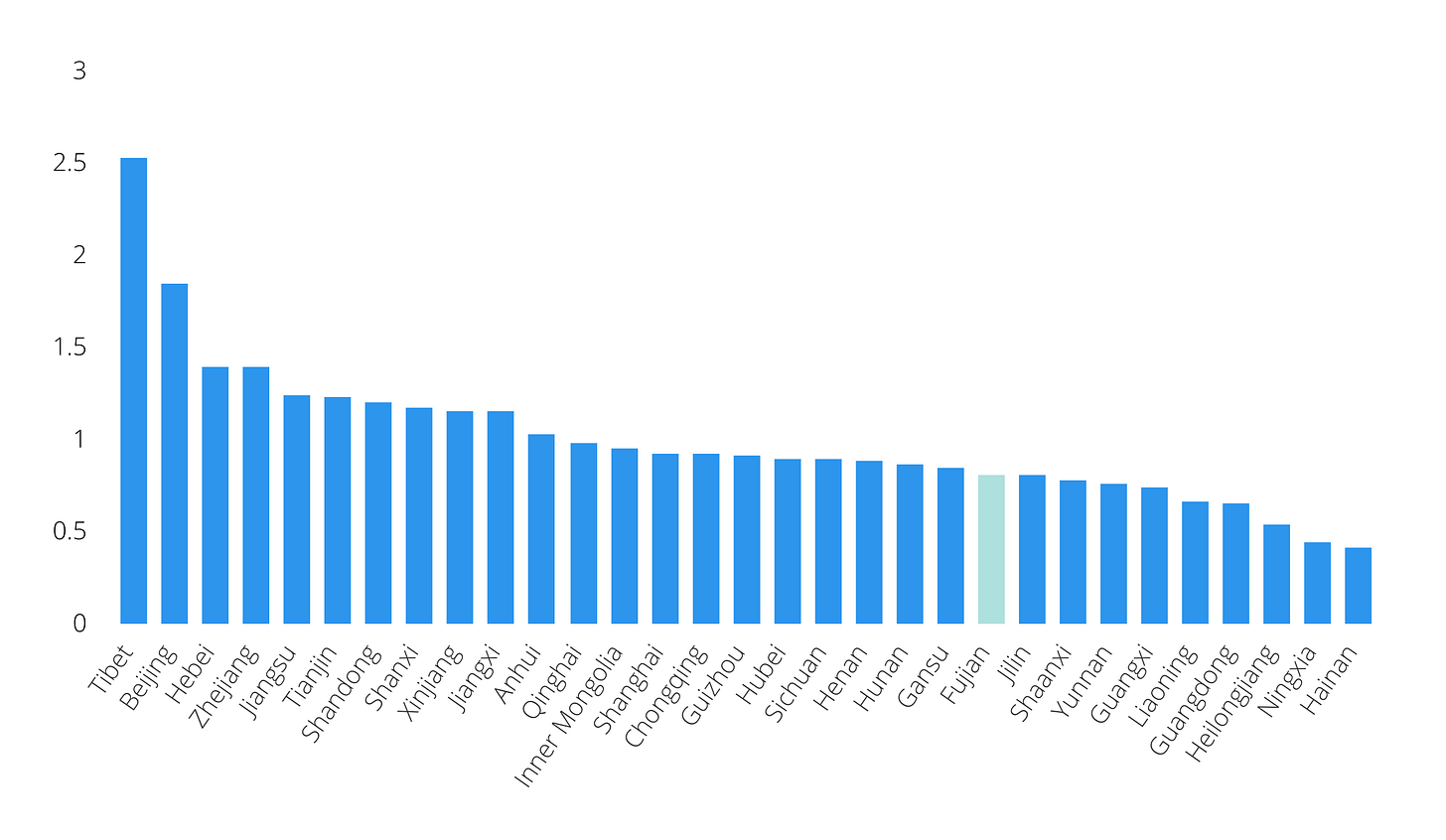

Now to see how land revenue has been inflated, it’s instructive to look at Fujian. The economically dynamic province should have pretty healthy demand for land, yet it appears to be punching below its weight in terms of generating land revenue relative to poorer regions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Fujian Is The "Norm” When It Comes to Generating Land Revenue

Note: Ratio for each region is calculated by dividing land revenue by property sales and averaged over 2017-2019.

Source: Wind and MacroPolo.

This seems puzzling at first but actually isn’t if you understand how land revenue has been distorted by the presence of local government financing vehicles (LGFVs).

LGFVs often need land as collateral to get loan approval from banks—more specifically, they need to show that a land transaction has actually taken place to secure the loan. So, local governments regularly engage in a fake land sale to the LGFV so that it gets a “receipt” to show the lender. That land is then eventually bought back by the local government after it has served its purpose.

We think this type of “virtual” land transaction explains much, if not all, of the variation in land revenue across China. For instance, one can see that regions with more LGFV debt, which is used as a proxy for LGFV land purchases, also have more inflated land revenue (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Level of LGFV Debt Positively Correlated with Inflated Land Revenue (% of GDP)

Note: Land revenue exaggeration is measured by land revenue/property sale. The higher the ratio, the more exaggerated the land revenue. Both this ratio and LGFV debt % are averaged for 2010-2019.

Source: MacroPolo.

So if this assessment is largely correct, then rather than being abnormal, Fujian is the norm. That is, Fujian’s LGFV debt/GDP ratio is less than 50%, about two-thirds that of the national average, which should minimize land revenue distortions. Meanwhile, other regions that have been inflating land sales should probably be a lot closer to Fujian in terms of land revenue.

Accounting for these regional distortions, as well as incorporating the property revenue exaggeration that matters for estimating land revenue, we think actual revenue from land sales is about 30% smaller than reported. To make that more concrete, land revenue in 2021 was closer to 6 trillion yuan (~$970 billion) rather than the 8.7 trillion yuan (~$1.4 trillion) in official figures.

Not a good sign for financial risk

As noted above, the systematic exaggeration of property and land revenue implies that the sector wasn’t contributing as much to growth in the first place. Therefore, the property sector’s slowdown is going to have less of an impact on growth than meets the eye.

To illustrate, after adjusting for compensation to farmers, net land revenue is likely less than 4% of GDP. Given that part of land revenue is allocated to repaying debt, land revenue financed less than a quarter of local government investment (~15% of GDP), smaller than usually assumed. Similarly, true property revenue was likely just 14% of GDP in 2021, rather than the reported 16%.

But this is no cause for cheers. Lower property and land revenue means that developers and local governments are more leveraged than they appear to be, given the amount of debt they’ve taken on to sustain the property sector as a whole.

Because the cushion offered by equity is so thin, the bulk of developers’ downside risk has been borne by their creditors. That risk falls primarily to the shadow banking sector because it is a major source of capital for property developers, along with housing presales. The formal state banking sector will be less vulnerable because it tends to finance local governments, which are more resourceful and can probably find ways to service their debt.

Shadow banking, on the other hand, will be in more trouble because developers are prioritizing appeasing consumers who made presale purchases over debt servicing. Beijing has also made it clear that it places consumers above shadow banking.

This situation isn’t going to turn itself around anytime soon, and in all likelihood will worsen as LGFVs are making more land purchases now that developers don’t have the cash flow. So to manage a soft landing in the property sector, as well as its ripple effects, will require delicate and skillful handling. That will be the subject of future research notes.

Wouldn’t that mean that GDP itself is two percent smaller than what is recorded in official statistics?